“The real secret of the ruby slippers is not that “there’s no place like home” but, rather, that there is no longer any such place as home—except, of course, for the homes we make, or the homes that are made for us, in Oz. Which is anywhere—and everywhere—except the place from which we began.”

Salmon Rushdie

Helen Edmundson’s adaptation of Andrea Levy’s acclaimed novel of the same name, Small Island, is faithful to the spirit of its source material if not slavish to its detailed design. We can assume this is due, at least in part, to the involvement of Ms Levy before her untimely death of three months ago. The source material has aged well. I have not read it since it was first published, and I was surprised by its contemporaneousness. Colourism, police brutality and a nation paralysed by its identity struggles are all found here. The centrepiece, however, is, of course, the momentous voyages of the HMT Empire Windrush, a history we are still writing today.

My description makes it all sound rather dour, but this could not be further from the truth; it’s hilarious. Levy’s follow-up to Small Island, the Long Song is one of my favourites because she manages to make a story set in the last days of Jamaican slavery, raucously funny. She brings that same humour here, not by creating caricatures or trivialising painful truths. But by asserting the humanity of her characters, the condition which allows us to find laughter, enjoy sex, and make light in the darkest of days.

Small Island is about the spaces we claim as our own and the negotiations that are required to hold on to them.

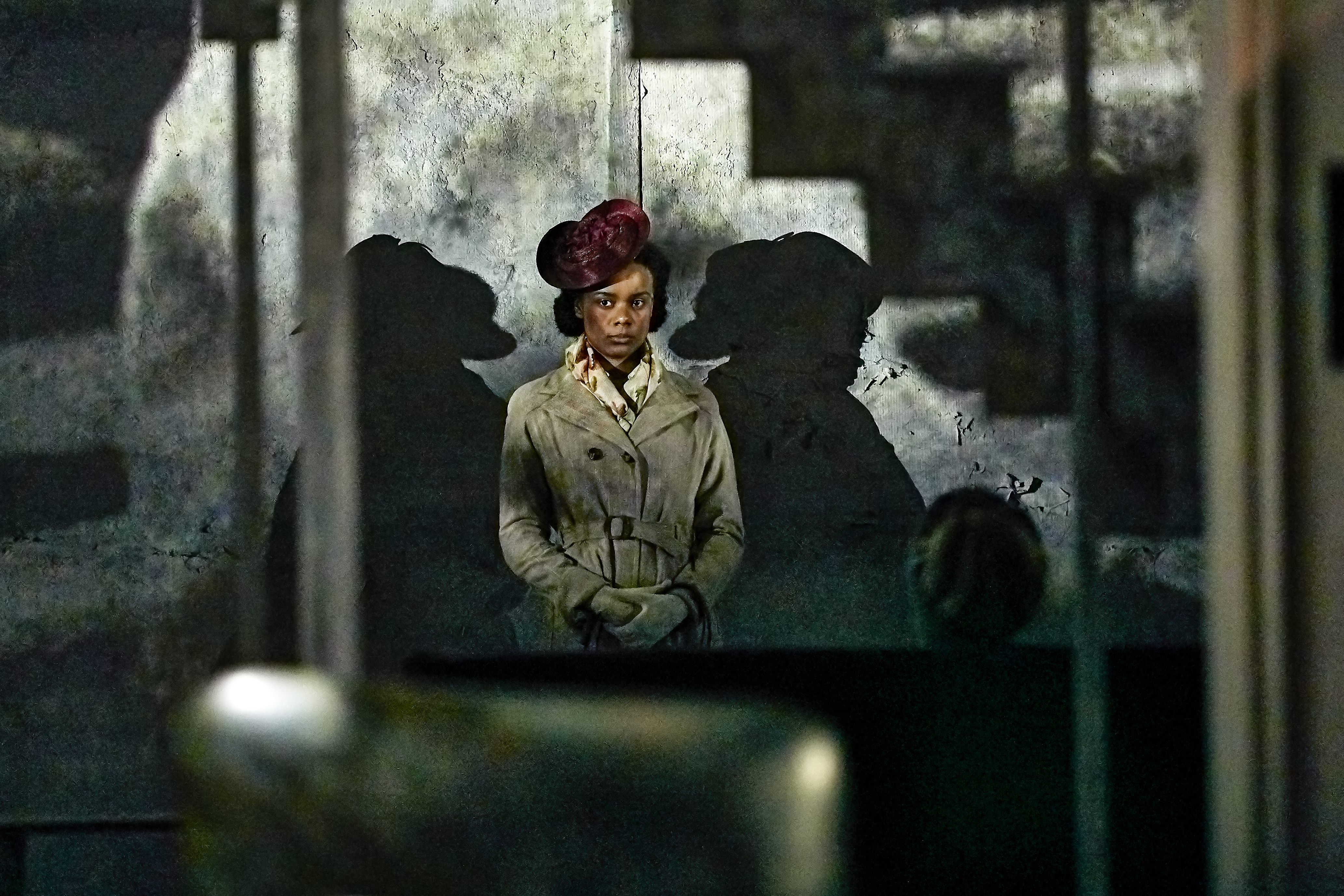

Its two female stars lead the comedy; Leah Harvey and Aisling Loftus. At times it feels as if you are watching a two-hander. Their male counterparts, especially Gershwyn Eustache Jnr’s Gilbert, are great fun, but both women turn in star-making performances. Aisling Loftus invites sympathy for her character Queenie I could not find in the novel. As the foil to Hortense’s restraint and reserve, she is all heart, humour and salt-of-the-earthiness. She would have stolen the show entirely for me if I had not recognised my mother in Leah Harvey’s intelligent interpretation of Hortense. Her performance deftly articulates the tension between the dampened dreams and learned resilience of any immigrant woman. The weight of the respectability politics that governed how first generationers navigated the hostile womb of the motherland is evident in her defiant posture and slow humbling. Hortense’s steadfastness to the lie of Empire, even when its ugliness is laid bare, is heart-breaking.

The singular scene of the play is arrived at the end of the first half, and achieved with simple but affecting production values, and a whole heap of empathy. Levy once wrote ‘every black person’s life, no matter what it is, is part of the black experience.’ The scene wordlessly speaks truth to her statement, conveying the aspiration and trepidation of all aliens so compellingly, it took my breath away.

I won’t spoil it, but if you are an immigrant, if you are a black body navigating whiteness, you will know it when you see it. In moments like this, when art deeply rooted in discretely black experiences is shared beyond the safety net of our community, I often wonder how the white people in the room are relating to the content. I’m anxious to both protect it from their uninformed gaze and win their approval (an unfortunate side effect of having too many experiences filtered through the white lens of diaspora living). But I didn’t get a chance to do this at Small Island; this was the blackest theatre night I have been to in a long time – and I write for Afridiziak.

Colourism, police brutality and a nation paralysed by its identity struggles are all found here.

The theatre brimmed with bougie black folk, giving a running commentary of “yas gal” and “nah son” and kissing their teeth liberally. If there was a culture clash playing out onstage, it was mirrored in the audience. White people politely observed the unspoken rules of the National’s rarefied air. Black people did not. Sitting in the National on an unseasonably, unreasonably muggy Wednesday evening in May, the differences between Britain’s early immigrants and us relative newcomers hung heavy in the too still, almost Caribbean air. This tension is what Ms Levy is most concerned with; reminding us that there is no single story of this nation or its peoples, but the central question of who belongs here and who does not continues to define it.

Small Island is about the spaces we claim as our own and the negotiations that are required to hold on to them. And this small island belonged to Hortense, to Gilbert and me long before we arrived here. On that night, buoyed by brilliant representations of the people whom we love, from the words of one of our best, we were reminded of that. We revelled in our proud tradition of call and response safe in the knowledge that there, in the stretch of London where art does not get higher, and white does not get whiter, there is confirmation that this small island is as much ours as it is anyone’s.

Thank you Ms Levy for your words, and for the gift of our story.

Small Island is at the National Theatre until 10 Aug 2019 |